The health ministry of Kenya said on Wednesday that the government and striking doctors had reached an agreement. The announcement came after nearly two months of strikes that caused thousands of patients to struggle to receive healthcare.

Health Minister Susan Nakhumicha told reporters, “After long and painstaking negotiations that ran into the wee hours of night for many days… we have signed a return to work formula and the union has called off the strike.”

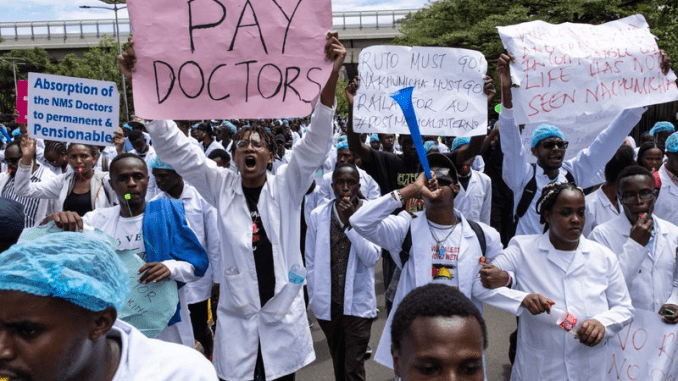

The action was started by the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union (KMPDU) in mid-March after multiple rounds of negotiations broke down over increased pay for interns, who make up around 30% of physicians.

The interns were previously to get a monthly stipend of 206,000 Kenyan shillings ($1,530) as per a 2017 agreement after an earlier walkout, but President William Ruto’s cabinet had previously declared it was “unsustainable” and had instead offered $530.

However, the doctors, who numbered around 7,000 in total, had promised not to go back to the bargaining table unless the interns’ agreed-upon salary level was reinstated.

A copy of the signed agreement that AFP was able to view indicates that the topic is still open, with the parties having agreed on Wednesday to “commence and conclude negotiations on the issue within 60 days”.

The agreement also states that all other doctors will return to work within 24 hours after the signing. “There shall be no deployment and or posting of medical officer interns, pharmacists interns, and dental interns” while discussions are ongoing.

The accord stipulates that the doctors will receive salary arrears totaling 3.5 billion shillings (about $26 million) over the course of the next five years. This sum reflects unpaid compensation hikes outlined in the 2107 agreement.

“Needs to Find a Long-term Solution”

Although the KMPDU secretary general Davji Atellah acknowledged that the strike was now finished, he told reporters that the matter over interns’ salaries was still “pending”.

“Despite having said and stated that we would not go home with promissory notes, we have decided to take the promise for the last time,” he remarked.

“I’m confident that this is a deal that will be implemented by all of us,” Nakhumicha declared.

“We must find a lasting solution to these perennial issues,” she stated.

The union was mandated by a labor court to put a stop to the strike in March. It then established several deadlines for ending the deadlock, the most recent of which was supposed to expire on Wednesday.

In Kenya, strikes against poor working conditions in public hospitals are frequent, causing a path of pain and frequently leading to the departure of Kenyan medical professionals to other African nations and beyond.

A 100-day statewide strike by doctors in 2017 resulted in the closure of public hospitals. Prior to the collective bargaining agreement being signed, dozens of people passed away from a lack of care.

However, physicians claimed that the government had broken some of the agreement, which is why they went on strike once more this year.

Kenya’s public hospitals were left operating with a skeleton staff throughout the eight weeks of industrial action, while people frantically sought care in the lack of physicians.

Water-borne Infections

Lobby organizations expressed worry that pregnant mothers were carrying the heaviest weight during the strike, citing the risks of handling cases requiring specialized treatment in the absence of physicians.

Kenyans’ health problems have been made worse by deadly floods brought on by heavier-than-normal rainfall, and the UN and nonprofit organizations have warned of the spread of cholera and other watery illnesses.

“The striking medical workers in Kenya have created a crisis in healthcare services that has been made worse by widespread flooding,” stated Jeffrey Okoro, executive director of CFK Africa, a non-profit organization that runs a maternity center in Kibera, the nation’s largest urban slum.

“Flood waters have mixed with pit latrines and the sewer system, causing a greater threat of waterborne diseases like cholera (an ongoing issue in Kenya), typhoid, and dysentery.”

Leave a Reply